Not by a Long Shot:

The Miscast Identity of Early Play Balls

This page is best viewed on a larger screen.

This article was researched and written by Jeffery B. Ellis, author of And The Putter Went Ping; The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs & Their History; and The Golf Club: The Good, The Beautiful & The Creative.

Copyright Jeffery B. Ellis 2025

These are simple play balls—

Bouncers of the pavement,

Magnets for busy hands,

Fancies of fledglings far and wide—

You know, toys.

There are many antique balls that can be confused with antique golf balls. At first glance, it's easy to mistake an antique play ball for a 19th or early 20th-century golf ball. They often share similar materials, shapes, and surface designs, but in reality, these balls were never meant for golf. Of the balls pictured above, only the one at the bottom is a genuine golf ball.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, a wide variety of play balls—balls made for children to play with or use in a game of some kind—were made from gutta percha and similar materials. They were part of a broader market for toys and games. This article aims to clarify the distinction between play balls and golf balls, offering insights to help readers better understand and recognize their differences.

Play balls in one form or another have been around for millennia, long before golf balls, but their paths crossed in an 1860 patent. Hamlet Nicholson's June 14, 1860 British patent No 1,478 was for a "New and Improved Cricket and Playing Ball [italics mine]." Nicholson described his method for constructing the inner body of the ball and explained that the outer covering was made from gutta percha or similar materials. His patent stated that his new compound ball could be used for a variety of games, including cricket and "goff" (golf).

Nicholson's patent allowed for the possibility of adapting his gutta-percha-covered cricket and play ball design to create a ball for "goff" (golf) or other games. However, there is no evidence that a golf ball was ever produced under this patent.1

Nicholson's patent underscores an important point: by 1860, play balls were being made with gutta percha exteriors surrounding a different interior material. Visually, these balls would often be indistinguishable from solid gutta-percha balls, complicating their identification. However, for the purposes of this article (at least at this early stage) the focus is not on whether the ball is homogeneous. What matters is that any ball—whether a play ball or a golf ball—with a gutta percha exterior requires closer examination to tell them apart.

Nicholson was not the first to mix play balls with golf balls, however. Credit for that goes to the Gutta Percha Company presented next.

1. The Gutta Percha Company Play Balls ↩

In 1842, Dr. William Montgomery, a Scottish surgeon working with the East India Company in Singapore, recognized the potential of gutta percha to make medical instruments and tools. He sent samples back to Britain. The first sample arrived in England in 1843, when Montgomerie presented the material to the Royal Society of Arts. It drew immediate interest for its unusual properties—particularly its moldability when heated and rigidity when cooled. With little delay, that initial interest grew exponentially.

The first manufacturing company to make play balls using gutta percha was the Gutta Percha Company of London. Founded in 1845, the Gutta Percha Company, quickly became the leading producer of gutta percha goods in Britain.2 Notably, they began selling play balls before they offered golf balls.3

This order of production is confirmed by a Gutta Percha Company advertisement placed in The Bristol Mercury, and Western Counties Advertiser on December 18, 1847. In it, the company listed goods "now ready" for sale—including "goloshes, bougies, stethoscopes, playing balls, medallions, and whip-thongs." The next paragraph outlined products still in progress: "tubing of all sizes, catheters and other surgical instruments, mouldings for picture frames and other decorative purposes, tennis, golf and cricket balls, &c." The implication is clear—the Gutta Percha Company's play balls reached the market before their golf balls. And while the two types of balls may look similar today, their intended uses were worlds apart. These early play balls were meant for the nursery, the playground, and the parlor—not the fairway.

By 1851, the Gutta Percha Company was advertising its play balls as "bouncing balls," emphasizing their resilient, elastic nature. Solid gutta-percha golf balls are also resilient, as hard as they are. A standing person can bounce one off a hard floor and catch it in their hand on the rebound. Advertisements from the time, however, don't clarify whether these play balls were solid gutta percha or simply coated with it.

One surviving example offers insight. The Gutta Percha Company play ball examined for this report has a gutta-percha outer layer applied over a hollow shell.4 Embossed with "Gutta Percha Company, London" and featuring a crest with a rampant lion and horse, the ball shows a substantial dent reminiscent of a dent on a ping-pong ball. A solid gutta-percha ball would have cracked or broken under that same stress, not collapsed inward.

Where the surface is chipped or worn, what is most likely some type of wood pulp product or papier-mâché reinforced with wood pulp (popular in England and France between the 1830s and 18970s) is visible beneath the gutta-percha layer. A solid gutta-percha ball would be the same material and color throughout. Although its 1.95-inch diameter is clearly too large for a golf ball, the most telling feature may be its weight—just 0.85 ounces. Despite its firmness and bounce, it's distinctly light. Place it in water, and it not only floats—but over half the ball is above the surface. This lightness was likely by design, a safety measure for indoor or child's play in case a game of toss-and-catch goes bad…

For comparison, a typical solid 1890s gutta-percha golf ball weighs somewhere around 1.37–1.47 ounces give or take. Of those that would float, and some would, only the very top of the ball would be above the level of the water. It’s been my experience that the oldest gutty balls will often weigh significantly more than 1.47 ounces5

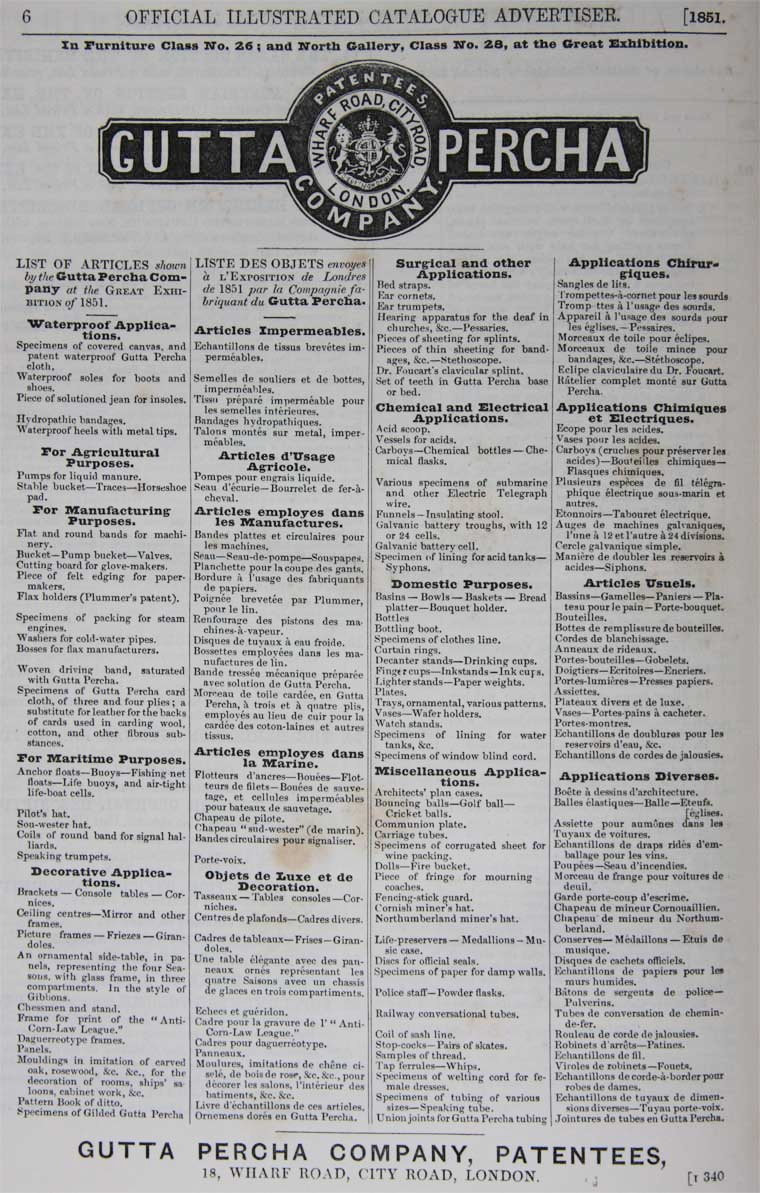

An 1851 Gutta Percha Company advertisement offering play balls ("bouncing balls" is under "miscellaneous applications" in the middle of the third column) is shown below. Directly below this ad are images of the actual Gutta Percha Company play ball discussed above, complete with its embossed name/trademark and a decorative design around the equator.

2. Mid/Late 19th-Century Play Balls ↩

During the 1850s, following the lead of the Gutta Percha Company, additional manufacturers began producing play balls. Below are just a few of the many references that document the widespread acceptance and production of children's play balls and various game balls made from gutta percha and other materials during the second half of the 19th century.

In the November 13, 1858, issue of the Northern Daily Times, Moseley & Company offered gutta-percha and vulcanized India rubber goods that included "children's play balls." Hellewell's of Liverpool advertised "New Fancy French India-Rubber Playing Balls, coloured and plain, all sizes and in great variety" in the January 20, 1859, issue of the same paper. John Mathieson's India Rubber Depot at 106 High Street, Dalkeith, advertised "…Bed and Crib Sheets, Nursing Aprons, Play Balls. A large and varied assortment of India Rubber Toys" in the May 16, 1878, issue of the Dalkeith Advertiser.

In the October 13, 1892, issue of the Barbados Herald, I. Sinderry Bowen offered celluloid play balls & colored balls.

The July 28, 1904, issue of Golfing contains a list of twelve balls that included at least two golf balls and "balls for other games" that were devised between 1844 and 1883. The list, while not exhaustive, demonstrates that there were many other balls besides golf balls being made in the second half of the 19th century.6

The Haskell Ball Company v. Sporting Goods Sales Company defendant's brief dated 1913, provides more evidence of gutta percha play balls. The defendants present a number of disclosures regarding various balls made during the 19th century that were enclosed in a "shell of gutta percha" as detailed in part in the next three paragraphs:

It is submitted that the disclosures to follow in the form of Letters Patent, testimony of witnesses, and tangible exhibits are convincing that this [shell of gutta percha], as well as the others of the claims of the patent in suit, was well known in the prior art.

Four separate letters patents were presented and discussed, one of which, the "US patent to Castle," specifically cites a gutta-percha-covered ball, made by a play ball manufacturer, used in a game that had disappeared by the 20th century:

There is considerable testimony in defendant's record relative to a ball, used primarily in the game of roller polo, which was manufactured by one Samuel D. Castle in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in the early '80s. Castle was engaged in the business of tanning hides, and conceived the idea of utilizing the waste scrap material in the manufacture of playing balls as an adjunct to the tannery. He adopted gutta-percha as the material for the cover. . . . Owing to the character of the cover, this ball "stung" the hands badly when caught and was extremely slippery when wet, and consequently attained little popularity as a baseball, but was extensively adopted in the game of roller polo, which thrived during the period from 1880 to 1885 or there-abouts.

As vulcanization techniques improved during the 19th century, manufacturers began using India rubber more often and gradually moved away from gutta percha. Around the same time, it became common to create compounds that blended one or both materials with various fillers and chemicals to reduce costs and improve the end product in some way.

When considering the variety of balls made during this period, it's important to remember that many only looked like they were made of gutta percha, but they weren't solid gutta percha at all. Furthermore, even if a ball was made entirely of gutta percha, that alone does not mean it was intended to be a golf ball even if similar in size.

3. Early 20th-Century Play Balls ↩

By the early 20th century, as India rubber firmly eclipsed gutta-percha in everyday use, play balls continued to grow in popularity. A January 1906 issue of The India Rubber Journal, under the title "Toy India-Rubber Balls," reports:

"'Sir.—An enquiry has been received at this Branch on behalf of a firm in Germany who wish to import large quantities of toy India rubber balls, plain and coloured from the names of the leading manufacturers in this country. I should therefore be much obliged for any names which you may be in a position to furnish.' Those of our readers who are interested in this matter should write to …"

Among the manufacturers who stepped in to meet this growing demand was F. A. Cigol of Paterson, New Jersey. Operating in the 1910s, Cigol produced, among other things, solid play balls made from various materials in various sizes and patterns. These balls—typically smaller than a regulation baseball but larger than a traditional marble—were often uniformly colored and lacked any outer covering. They echoed the solid construction of their 19th-century predecessors but benefited from improved rubber processing methods that enhanced elasticity (at least when they were first made). Cigol's offerings serve as a tangible bridge between the gutta-percha and India rubber play balls of the Victorian era and the synthetic rubber balls that would later dominate toy markets in the mid/late 20th century.

3.1a F.A. Cigol Play Balls ↩

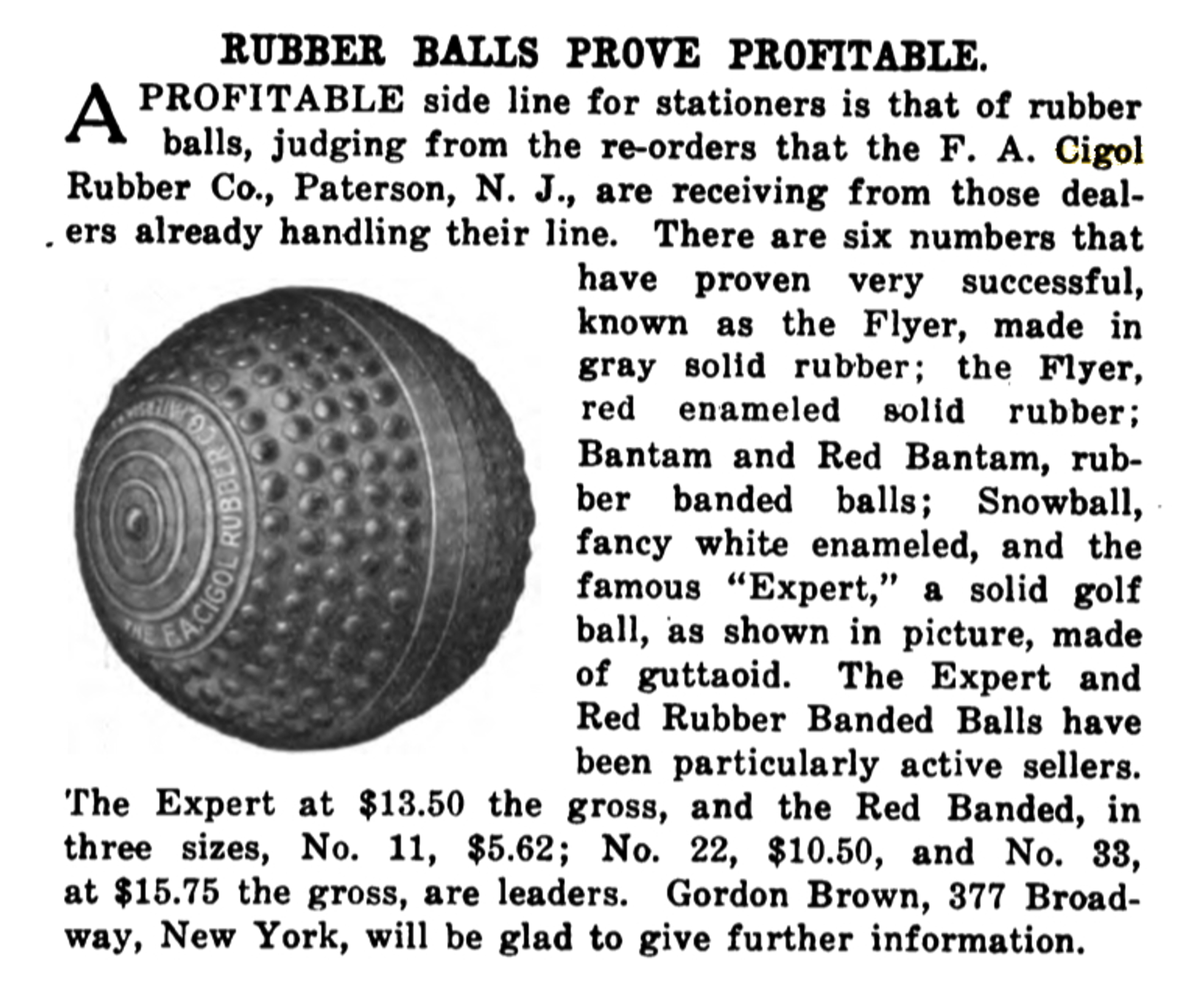

The November 21, 1912, issue of Geyer's Stationer includes a notice of five different rubber play balls and one "guttaoid" ball offered by F.A. Cigol Rubber Co. A copy of the notice is shown below.

Of particular interest is the Expert ball—Cigol's "solid golf ball made of guttaoid." Priced at $13.50 per gross, the Expert cost just $1.125 per dozen, or approximately 10 cents per ball.7 By comparison, Spalding's Official Golf Guide for 1911 lists the cheapest genuine golf balls at $7.50 per dozen, or about 63 cents per ball. This vast price difference reflects the reality that the Expert was not a bona fide golf ball; it was merely designed to resemble one. While it could technically be used on a golf course, its performance would have been exceedingly poor. The balls were notoriously inconsistent in weight, with some examples dramatically heavier than regulation balls.

The Cigol "golf design" Expert ball was produced in various sizes and differed in both material composition and, I believe, internal construction. Some were possibly hollow at the core, while others featured a heavy interior. For this report, four Experts were weighed. Two fell within the lighter end of the golf ball range, at 1.38 oz. The remaining two, which exhibited no noticeable bounce, were roughly twice as heavy—registering 2.56 and 2.76 oz. Their diameters were 1.55, 1.62, 1.63, and 1.67 inches, respectively. Though all four could theoretically be struck with a golf club, the two heavier examples would lead both the golfer's score and their wood-shafted clubs to ruin.

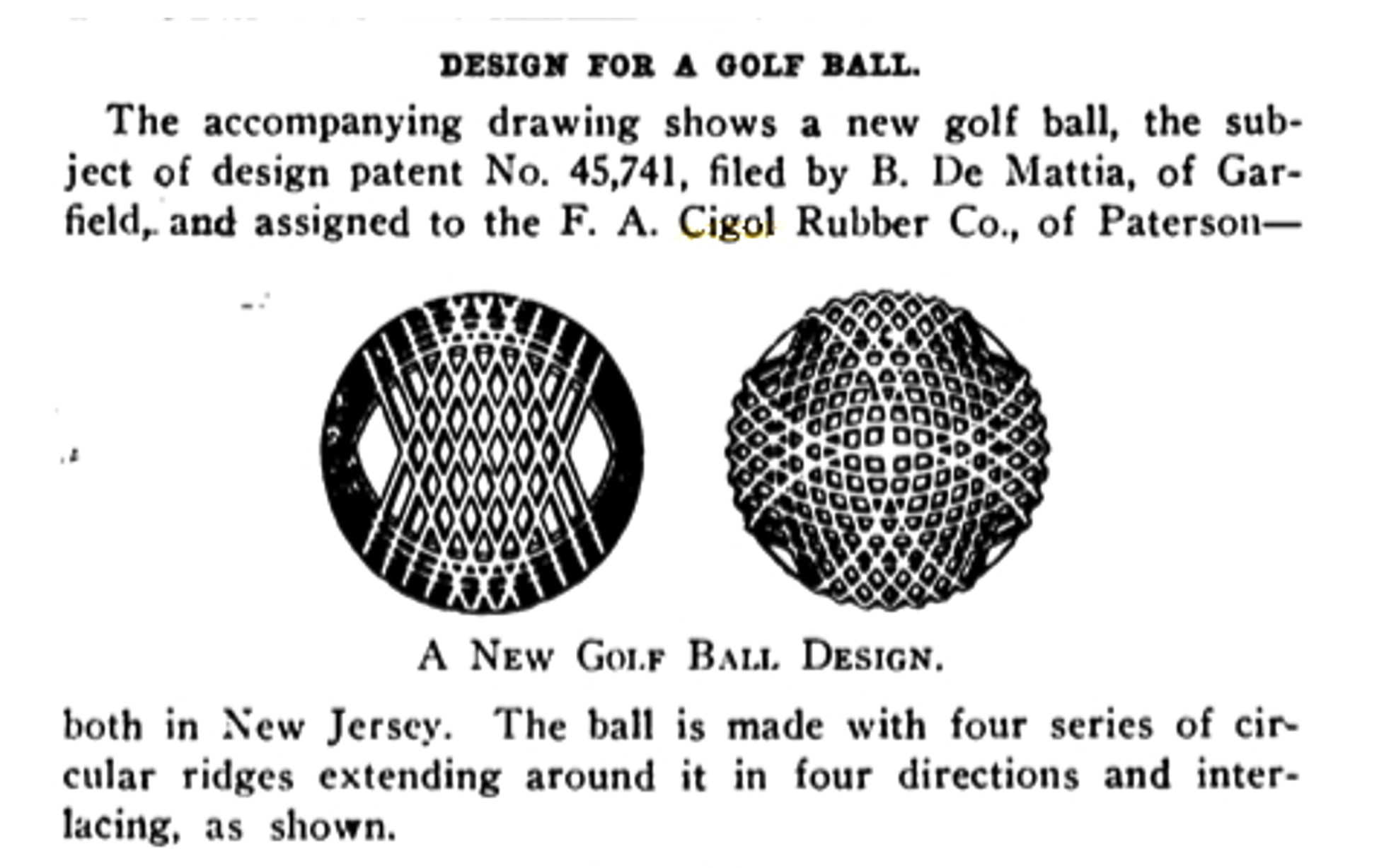

The above notice published in the August 1914 issue of India Rubber World introduces a newly patented "golf ball" assigned to the F.A. Cigol Rubber Co. Despite being referred to as a golf ball, this bouncer was likely not intended for use while golfing but instead featured a unique golf-ball–like design consistent with Cigol's focus on toy manufacturing.

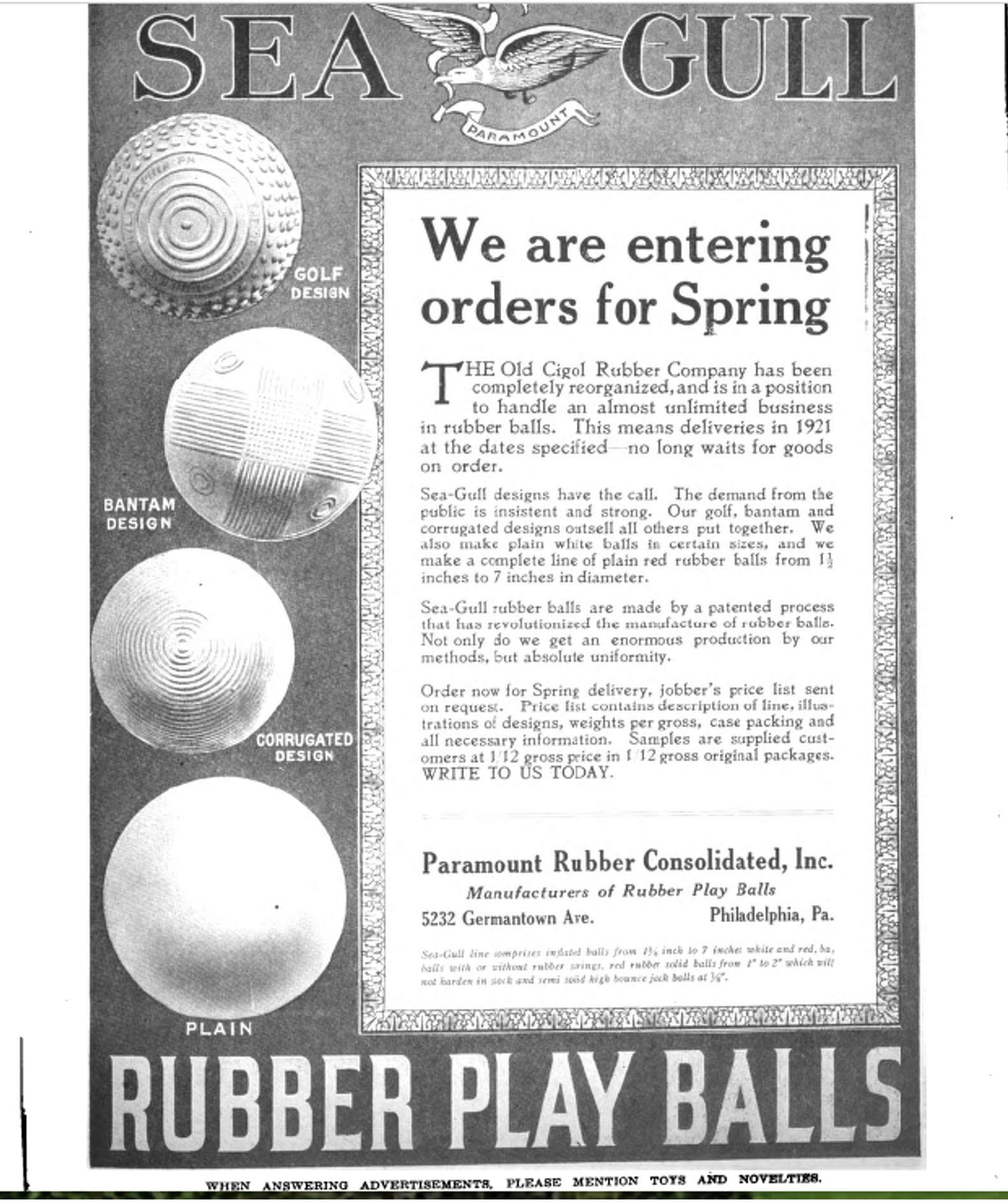

By 1920, the F.A. Cigol Rubber Company, along with the Paramount Rubber Company and the Aranar Company, had been absorbed into Paramount Rubber Consolidated, described in the April 10, 1920, issue of The American Stationer and Office Outfitter as "a large manufacturer of toy rubber balls."

3.1b Paramount Play Balls ↩

Later that year, Paramount Rubber Consolidated began marketing "Sea Gull" (a whimsical nod to "Cigol") rubber play balls. These were available in at least four designs: "Golf Design," "Bantam Design," "Corrugated Design," and "Plain." An advertisement in the November 1920 issue of Toys and Novelties notes that plain white balls were made in various sizes, and plain red balls ranged from 1½ to 7 inches in diameter.

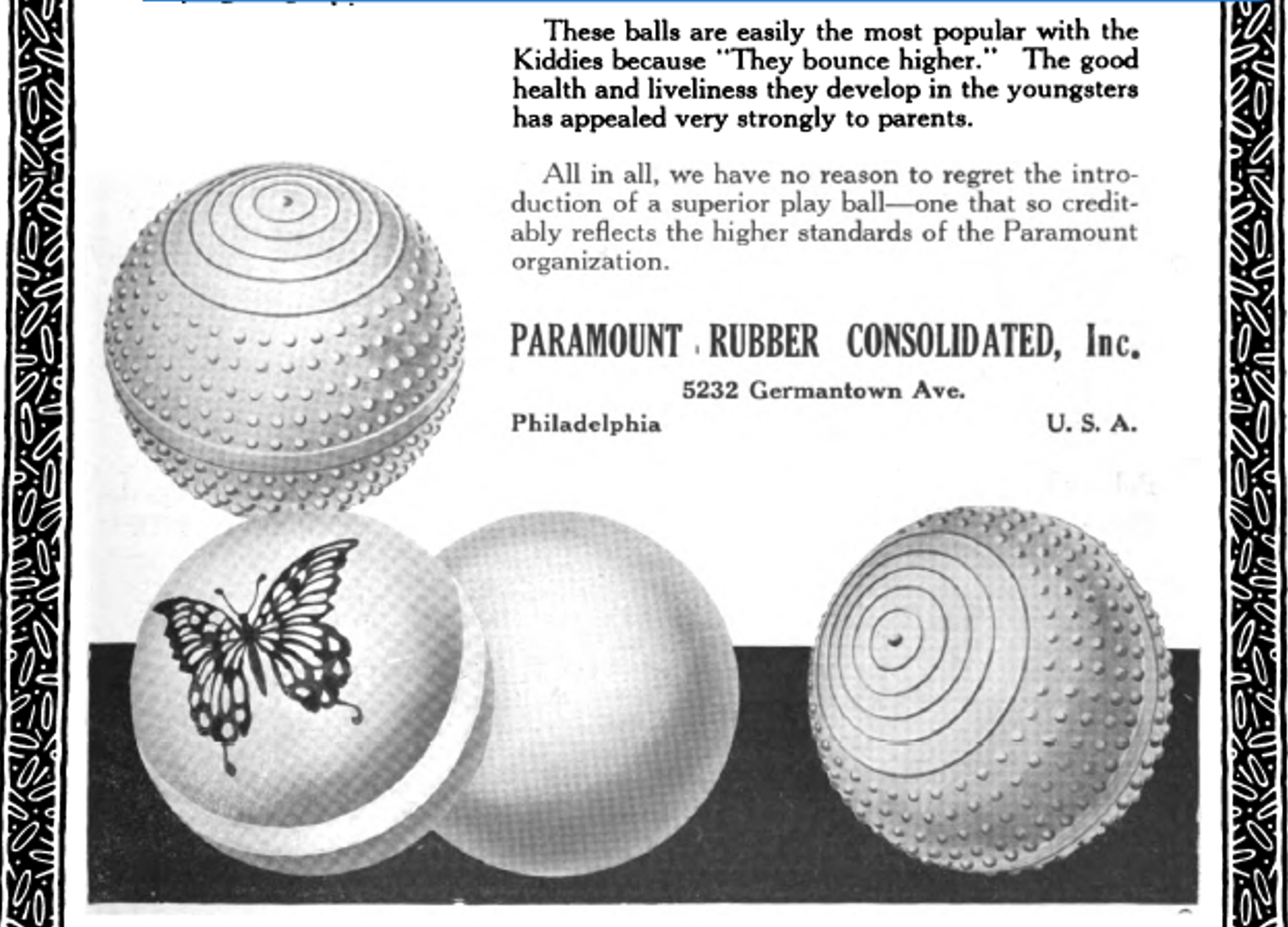

The advertisement below features Paramount's version of Cigol's Expert ball—notably without the Cigol name on the pole—alongside another ball with a smooth surface. The ad proclaims, "These balls are easily the most popular with the Kiddies because 'They bounce higher.'"

A Paramount rubber ball display, featuring actual rubber balls, shows that they were made in various sizes, with some plain examples left unpainted.

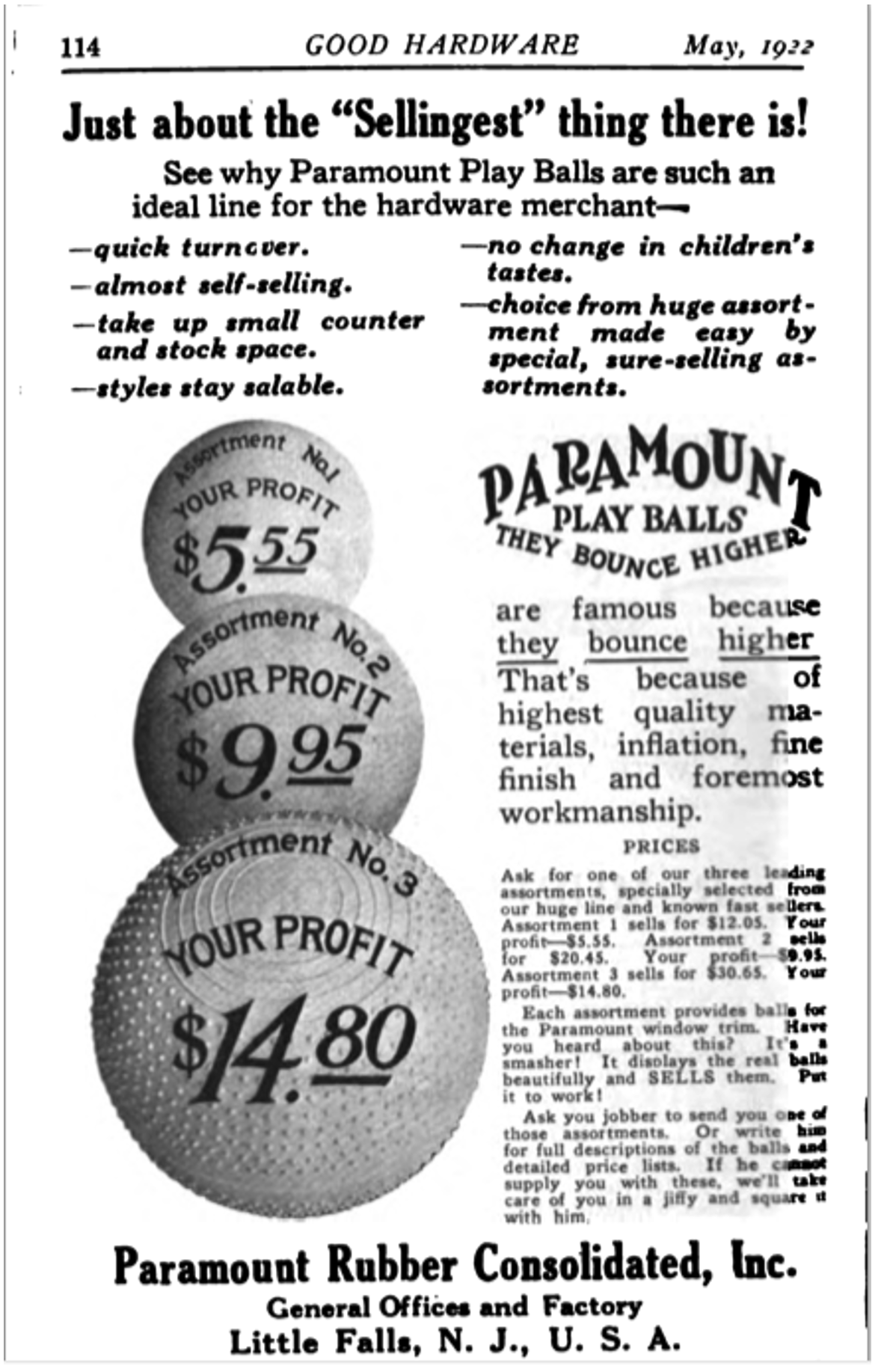

Business was thriving for Paramount Rubber Consolidated. As the May 1922 advertisement below notes, the company had developed a "huge assortment" of rubber balls, available for purchase in three different assortments. An earlier ad from that same year also highlights that they were offering both solid and inflatable rubber balls.

The fact that none of Paramount's balls were intended as golf balls is evident not only from their advertising but also from their physical characteristics. They vary widely in size and weight and, today, often display little to no resilience—traits inconsistent with true golf balls. When located today, Paramount balls, like most other antique rubber play balls, have become hard and any exposed rubber is dark in color and sometimes appears much like gutta percha.

4.1 Golf Ball and Play Ball Sizes ↩

Shown below are nine solid play balls made from gutta-percha, India (para) rubber, and various composite materials, and one genuine golf ball. These play balls came in a range of sizes similar to a standard golf ball—a 1913 Chemico Bob golf ball is back left—with some larger and some smaller.

While there were no formal regulations governing golf ball size in the 1910s, a generally accepted size range had long been established. When the USGA and R&A formalized the modern rule in 1974, the smaller British ball—typically measuring 1.62 inches in diameter—was declared non-conforming. From that point forward, golf balls were required to be no smaller than 1.68 inches in diameter, aligning with the size long accepted in the United States.

In the early and mid-19th century, however, golf ball sizes showed greater variability. For example, an entirely handmade Allan Robertson feather ball I recently measured was 1.82 inches in diameter between the poles and 1.76 inches at the equator. A circa 1870 hand-hammered gutty came in at 1.73 inches. By the 1890s, this range had narrowed. Three balls measured for this report illustrate the trend: a c.1890s Silvertown measured 1.70 inches, an 1899 Vardon Flyer was 1.69 inches, and the Chemico Bob shown in the back left corner of the image above measured 1.67 inches.8

5.1 Smooth Balls ↩

In the world of golf ball collecting, smooth balls often attract keen interest. That's because smooth gutta percha golf balls from around 1850 carry significant historical value and can command high prices when sold. As a result, any smooth ball similar in size to a golf ball is frequently—and often mistakenly—presented as a rare treasure: a "smooth gutty from 1850." But just as with real gold, collectors must learn to distinguish genuine finds from fool's gold. To that end, the following section will highlight smooth balls that are not golf balls. The section after that will focus on authentic c.1850 smooth gutta percha golf balls—most of which I am intimately familiar with and have personally examined.

5.1a Smooth Play Balls ↩

Shown above are five smooth play balls along with, third from the left, a mesh-pattern Silvertown golf ball from the 1890s. The ball at the far right is made of solid gutta-percha9 and measures 2½ inches in diameter—well beyond the size of any regulation golf ball. While too small to be a traditional croquet or boule ball, it may have been intended for another type of game. It would certainly function well as a rolling play ball, though it's equally possible it was made for a now-forgotten purpose. What's clear is that solid balls were produced in a wide range of sizes for use in games that are no longer played and have faded from public memory.

The second ball from the right is the mid-1800s play ball produced by the Gutta Percha Company discussed earlier. It consists of a hollow shell coated with gutta-percha.

The appearance of the two smooth, medium-brown balls flanking the Silvertown mesh ball is not consistent with solid gutta-percha. Although both are hard and similar in feel to pure gutta-percha, their speckled coloration suggests they are made from a compound material rather than the uniform, solid color typical of mid-19th-century gutta-percha golf balls.10 Instead, they appear to be composed of a composite blend that includes additives and/or chemicals mixed with India rubber, gutta-percha, or both.11 One ball weighs 1.43 ounces, which falls within the standard range for a golf ball, while the other, at 1.26 ounces, is too light. These could have been manufactured by Cigol, Paramount, or any number of other play ball makers active during the period—of which there were many.

The orange ball at the far left is dark beneath its surface coating, resembling gutta-percha in appearance. However, at just 1.563 inches in diameter, it is significantly smaller than a standard golf ball and was likely not intended for golf. The orange and both medium-brown balls are solid and share the sound and bounce characteristics of gutta-percha golf balls (as well as the largest ball above) when lightly dropped from a height of about ¼ inch onto a hard surface. The GPC play ball has a nice click, though its pitch is slightly, yet noticeably, higher than that of a solid gutta-percha golf ball.

Below are several balls with smooth surfaces, many of which appear to be play balls. As none of these have been in my possession, I cannot provide details on their size or weight. Nevertheless, I am reviewing them here as if they are the correct size, and even then, simply the appearance of most is sufficient to indicate that they are not genuine antique golf balls.

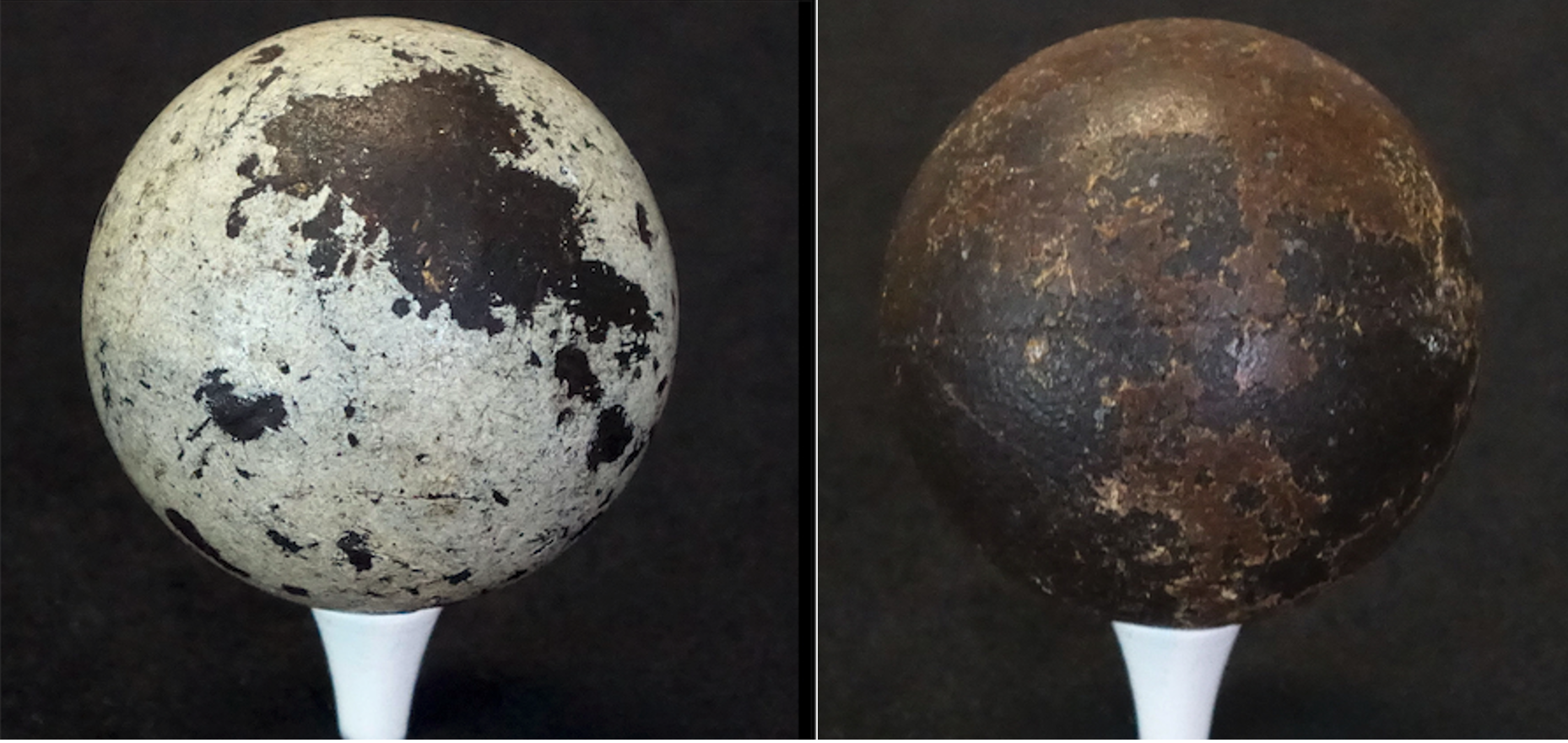

These two balls are not consistent with the color of solid gutta percha golf balls from the 1800s. Furthermore, the ball on the left has filler mixed into its material, and the ball on the right is a different, lighter color where the cover is scraped (as can be seen in two spots near the top of the ball). In contrast, a solid gutta-percha ball from the 19th century is uniformly dark in color throughout, with no variation between the surface and the interior.

The exposed area under the paint on the ball on the left does not match the color of the gutta percha used to make smooth gutties. The ball on the right is cracking as if it has a cover of some kind, something not found on any known gutta percha golf balls produced in the 1800s.

The exterior cover on the ball at the upper left is white both on its surface and in areas where it is worn, while the exposed material at the equator has an orange hue—neither characteristic is consistent with gutta percha.

As for the ball at the upper right, the small black marks may be chips in the paint revealing gutta percha beneath, though it's unclear whether these marks are actually chips. Even so, the ball appears too refined to be 175 years old. I do not know of a painted smooth gutta percha ball from the 1850s that has survived to the present day without significant paint loss. Moreover, the paint used here does not resemble the old lead-based paint typically found on golf balls from that era—at least not in my experience—nor does the wear and dirt on the paint have the look of great age. In short, nothing about this ball says it is from 1850 other than it might be the same size as those that are, and given that I have not measured it, even that might not be correct. But it does look very much like another game ball coming up.

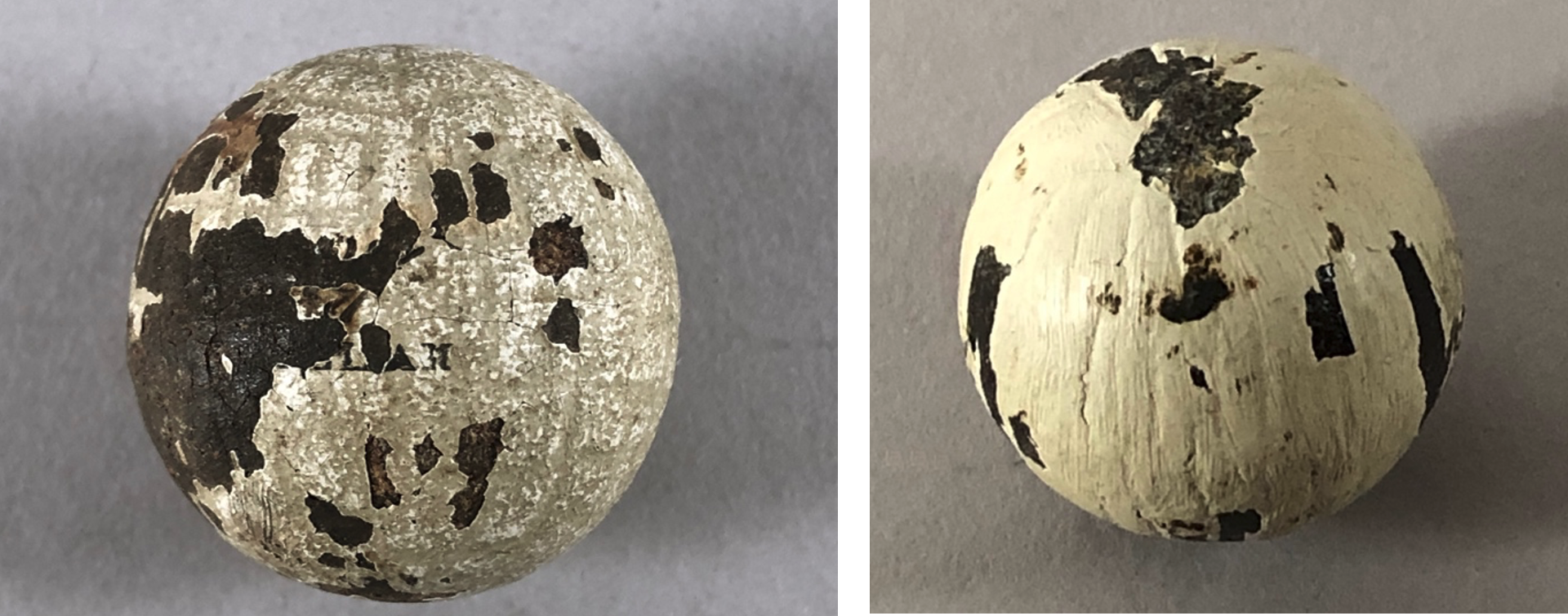

The two images above show the same ball. The image on the left is not as sharp or bright as the one on the right, which reveals the remains of circular rings around the center of the ball. Smooth gutties never featured such rings, but such was a natural for 20th- century play ball. With its speckled light brown appearance, this ball is made from a composite material, likely a mix of gutta percha and/or India rubber combined with additional fillers.

During the 1880s, a small number of composite golf balls, made from gutta percha mixed with filler material, were produced. However, by this time, all golf balls had long featured patterned surfaces. The composite Eclipse golf balls of the 1880s and 90s still appeared to be made entirely from gutta percha. The filler material in these balls was likely ground into powder and processed to 'disappear' when mixed with the gutta percha. (There are no visible fragments or bits in the uniform, unpainted surface of an Eclipse to suggest the presence of any additives.)

The two pictures above show the same ball. As seen in the image on the left, the surface of the ball appears to be gutta percha. However, the image on the right reveals that the interior of the ball is made of a composite material (note the speckled pieces of filler), which differs in color and appearance from solid gutta percha. Genuine smooth gutta percha golf balls from the 1850s were not manufactured with outer layers or coatings of gutta percha; they were solid gutta percha throughout.

As mentioned earlier in this report, between 1860 and 1890 there were various balls patented and produced that either called for or used a gutta percha cover. However, no golf balls of this construction made prior to the Haskell ball patented in 1899 are known. Even if gutta percha-covered golf balls were made in 1860 or thereafter, their surface would not be smooth like the ball in question. By the early 1850s, it was well understood among golfers that scored—or textured—surfaces improved flight, and such designs quickly became the standard.12

The ball on the left features a raised fin around its equator—a detail sometimes seen on authentic smooth gutta-percha golf balls from around 1850. However, it also has molded "bands" positioned above and below the equator. The purpose of these bands is unclear, possibly decorative, but they are not characteristic of smooth gutta-percha golf balls from that era. More significantly, the ball lacks the distinctive shine and plastic-like appearance of unworn gutta percha. Instead, it appears to be made of rubber, not gutta percha.

The ball on the right does exhibit the shine and plastic-like appearance typical of gutta percha and is likely made of that material. It is deformed in several places but shows no strike marks consistent with being hit by a golf club. While heat can cause a gutta percha ball to deform, that alone does not rule it out as a golf ball. However, it's impossible to determine from this image whether the ball is 10 years old, 50 years old, or more than a century old. A proper evaluation would require examining the ball in person—assessing its weight, size, resilience, and compressibility. Any one of these factors could reveal that the ball was not intended for golf. Furthermore, the absence of oxidation or surface cracking may point to a more modern origin.

The ball on the left more closely resembles the typical color of India rubber rather than gutta-percha. Furthermore, there appears to be zero crystallized material where a piece of the ball has broken away. Such would not be the case if the ball was made from gutta percha 175 years ago (examples coming up).

The ball on the right still retains traces of white paint, but the paint appears relatively fresh and bright, not old. Additionally, the material may be celluloid, a form of which was used to make a small number of golf balls in the 1890s, or Bakelite, used extensively over a century ago to make billiard balls. It may be ebonite, a hard rubber used to make bowling balls. A hands-on examination would be necessary to more accurately identify the material used to make this ball and its possible age.

Above, to the far left and far right, are two smooth balls. Both are the size of a golf ball. The red ball (red c.1850 golf balls were used in snow and frost) on the left has remnants of a mold line around its equator, while the white ball has specks of dark brown (the color of gutta percha under the paint on a genuine c.1850 gutta percha golf ball) and hairline cracks on its surface (gutta percha can dry out and crack). Neither of these balls, however, is a golf ball, smooth or otherwise. When either ball is lightly bounced, it produces an extremely hard sound, like a billiard ball. This is because both balls were made for bagatelle, a game very similar to billiards.13

Centered above the two balls is an old ball made out of wood, and it makes a very bright click when lightly bounced, as hard wooden balls do.14 Wood balls were used in 19th century bagatelle games, and, no doubt, in others. Compared to Bakelite bagatelle balls of the same size, wooden ones are lighter, and their click is not quite as high in pitch. The mesh pattern gutty ball is a genuine golf ball shown for reference.

Bagatelle is a tabletop game that originated in France in the late 17th century and became widely popular in Europe and North America, especially during the 19th century. The game is often considered an early precursor to modern pinball. Bagatelle balls came in sets with diameters ranging between 1 and 2 inches.15 During much of the 19th century, bagatelle balls were made from ivory, but this changed with the advent of Bakelite. This is just one of many games played a century or more ago that used a hard, small ball with a smooth surface.

Above, the ball on the far left isn't quite the right color for pure gutta-percha as used in 18th-century golf balls—or is it? Photos don't always tell the full story, which is why a physical examination is so important. Based on the photo, maybe it is an old smooth gutty ball, or maybe it's not. Each collector is sometimes left to their own devices, advisors, and comfort level when determining authenticity.

The ball on the far right is much closer in color, but both it and the red ball in the middle are wood replicas of smooth gutty balls.

The ball shown twice above appears to have some age, but the nature of the blemishes on the surface is inconsistent with the way gutta percha typically ages. The ball as shown on the left has two "creased" or sunken areas where the ball appears "smushed," and there are numerous holes and pits scattered across its surface. The white color of the cover remains intact, even around the upper sides of the holes. The cracks in the surface of the ball in the right-hand image are significant, but again, there is no loss of paint. None of these characteristics align with those found on a genuine smooth gutty ball.

Genuine gutta percha balls do not pit in this manner; instead, they often bear distinctive strike marks from being mishit by a golfer, which are not found on this ball. Gutta percha is brittle by nature, it does not smush from use. If this ball was painted, as a genuine gutta ball would be to appear white, much of the paint would have chipped off around any damage. The exterior of this ball appears to be made from a white material that is much thicker than a typical coat of paint. In short, while the ball shows age and distress, the distress is not consistent with the aging process of a solid sphere of 175-year- old gutta percha.

The yellowed smooth ball above shares the same issues as the earlier one. It shows signs of age, cracks in the surface, and wear, but the nature of the distress does not align with what typically happens to an old gutta percha ball when it becomes worn and damaged. However, an obvious tell is at the top of the ball, where part of it has come apart and extends above the rest of the surface.

Note that the exposed side of this piece is white, just like the surface (though yellowed with age). This indicates that the exterior of the ball is a white layer of material, and that is inconsistent with a genuine smooth or any other solid gutty ball. If a gutty ball has a white exterior, it was only because it was painted white. Because there is no paint damage around any of the damage on this ball, and there is a lot, we know this ball is neither painted nor made from gutta percha.

Lots of good things about this ball! It has old paint, some of which has chipped off to reveal what looks like old gutta percha underneath. The ball looks old, and it’s the right size, etc. But…wait…there’s more. Upon close inspection under excellent lighting, as shown in the photo above right, vertical lines can be seen on the side of the ball, intersecting the seam line around the equator. (I examined this ball for a minute or two before spotting these lines. The photo makes them appear much easier to see than they actually are.) The presence of a mesh pattern indicates that this ball was made in the late 19th century, when molded mesh gutta percha balls were the most popular style in use.

Why does this ball look so much like an old smooth gutty? In restoring this ball back in the day and trying to give it new life, the owner of this ball sanded/filed the surface to make it a little smoother—no harm in smoothing out a few nicks and dings—then repainted it using a lot of paint. Repainting a worn ball was something golfers occasionally did back in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Yes, this ball is a genuine gutty ball, but not a c.1850 smooth gutty.

The ball on the far left is a verifiable c.1920 play ball. The one next to it shows wear consistent with similar use, and its color/material does not match that found on known smooth gutta-percha golf balls produced in the mid-19th century. Additionally, both appear to be far smaller than a standard golf ball. The smooth ball on the right may be an old practice golf ball, as it remains flexible and lightweight, but it could just as easily be an old play ball.

The ball on the left is the correct size for a golf ball, but its surface is deteriorated consistent with that of a gutta percha golf ball that has been buried in the ground for many decades. Any original markings—such as a mesh or other pattern—have long since disintegrated, making it impossible to determine anything about this ball. As it stands, it's simply an unidentifiable golf ball in about as poor condition as one can be.

The ball on the far right has the correct color and appearance of gutta-percha. It may be old or it may not. Its condition is consistent with that of a well-preserved smooth gutty, but questions remain: Is it a replica? Is it actually made of gutta-percha? A physical examination would be imperative to make an accurate determination. It's worth a closer look, recognizing all the while, that a smooth gutta percha ball is easy to replicate/fake.

Antique and vintage smooth balls that remain today vary in texture, color, and color uniformity. Because of this, it is easy to rule out a ball as a 19th-century smooth gutty when the material, color, or uniformity of the color are not consistent with that of an antique smooth gutty golf ball.

5.1b Genuine c.1850 Smooth Gutta Percha Golf Balls ↩

Having already highlighted several smooth play balls that have been misidentified as early golf balls, I will now present eleven authentic smooth gutta percha golf balls, all dating from the mid-19th century. Also included are four line-cut gutties, three hand-hammered gutties, one feather ball, one bramble gutty, and two early rubber core bramble balls with gutta percha covers22 Together, these nineteen examples illustrate the key visual characteristics of genuine 19th century gutta-percha golf balls: their material composition, natural (unpainted) color, surface oxidation, and any paint that may have been applied.

From the outset, it's important to recognize that smooth gutty balls are especially difficult to authenticate because they are easy to fake. Authentic mesh-patterned balls can be sanded down or even re-molded using a smooth ball mold. That's why collectors must pay close attention to all aspects of a ball's appearance and construction. In doing so, one should always weigh the probabilities—asking, "What are the chances that each feature of this ball is genuinely old?" and "What evidence supports its age?" Of course, an impeccable provenance is a stellar feature, as shown below.

The two images above are of the same genuine c.1848 smooth gutty ball. This ball bears the label of Harry B. Wood who assembled his golf collection prior to documenting it in his book Golfing Curios and the Like published in 1910. Gotta love everything about this ball.

Above is a second smooth gutty ball from the Harry B. Wood collection. This ball illustrates the hairline cracking that can occur on the surface of gutta percha over time. These cracks are often a result of both the natural aging process and environmental factors.

As gutta percha is an organic thermoplastic, it can be heated, molded, cooled, and then reheated, remolded, and cooled again without significant degradation, which gives it a high level of reusability. However, this ability to be reformed/remade does not make it impervious to all forms of deterioration. One such form is oxidation. When exposed to oxygen and environmental elements over long periods, gutta percha can undergo chemical changes. The surface may show signs of oxidation, often appearing as a yellowing or discoloration, and in some cases, the formation of cracks as the material becomes more brittle. These cracks can serve as visual indicators of age, revealing how the material has reacted to its environment over time. This is especially significant for golf balls made from gutta percha, where the surface wear tells a story of their longevity and exposure to use and time.

Both of these smooth gutties were part of the Hope-Ware collection purchased in 1926 by Joseph Sartori, who donated it to the Los Angeles Country Club. Sartori traveled to the UK and returned with golf treasures that included a large part of the famed Andrew Forgan golf ball collection. The gutta percha in both balls looks the same, but the original white paint on the second ball has darkened a lot. This is likely due to a chemical reaction in the lead-based paint. As I understand it, over time, the lead in the paint can react with substances in the air—like sulfur—to form lead sulfide, which turns the white lead paint dark.16 I have seen this in varying degrees on a number of other balls. These are beautiful balls with a fabulous provenance.

The ball shown twice above is made from gutta percha with lines cut into its surface to resemble the stitching pattern of a feather ball. It is believed to be one of the very first gutta percha golf balls made by John Paterson—the same Paterson credited with selling the first gutta percha golf balls. According to the June 15, 1901, issue of The Scotsman,"When Paterson's ball was first made, the surface was perfectly smooth, and marked only by lines, engraved by the turning-lathe, in imitation of the seams of the old leather. It did not fly well when new, but did better after being well hacked. This suggested hammering."

James Forgan confirmed this in the December 27, 1907 issue of Golf Illustrated: "The oldest gutta-percha golf balls I have seen were formed as [much] like the feather ball as possible, with a slight groove like the seams of the skin of the feather ball, and were stamped with the name John Paterson."

As shown above, the balls Forgan referenced were apparently stamped "Paterson New Composite." To gutta percha golf ball collectors, the name-stamped and feather-ball-cut Patterson balls are the pinnacle of smooth gutties, because they were the first.

The gutta percha golf ball was invented by Robert A. Paterson who tried it on the links of St. Andrews in 1845. John Paterson, Robert's brother living in Edinburgh, improved the ball—made it more durable and less susceptible to cracking—and produced the first ones ever sold. In 1846, several dozen were sent to London and St. Andrews, where they were offered for sale:

"R.A. Paterson, the boy, left some with Melville Fletcher, south Street, and Joseph Cook, Market Street, booksellers, and they lay ignominiously in the window and were finally dusted out. He then took them to Mr. Stewart, at the time in charge of the old 'Union Golf Parlor,' St. Andrews, and with the daring of an unsophisticated boy ran over to 'Allan Robertson's' where 'Tom Morris' and 'Allan' were shoving feathers into queer looking skins, and 'Allan' gave the Guttas a good examining, and then showed the whites of his great handsome eyes, but never spoke a word. 'Tom Morris' rolled the white balls over and over, and handed them back all thumb marks to young Paterson….This was on the eve of young Paterson's going to America" (St. Andrews Citizen, 25 Oct. 1895. See also The Clubmakers Art, Second Edition, Vol 2 p 762 for additional information).

Above left is an unpainted smooth gutta percha ball property of The British Golf Museum. The smooth gutty on the right still has its original paint. In places where the paint is missing and the surface of the ball has been disturbed, the gutta percha has begun to dry out, oxidize, and crack, which is what happens to gutta percha when it begins to deteriorate. Gently rubbing these areas will result in tiny grains of "crystallized" gutta percha falling off the ball. (You really don't want or need to do that, because its crystallized nature will appear obvious upon close inspection.) Plus the original white paint on this ball is old and has yellowed, evidence of lead sulfide caused by the oxidation of white lead paint as explained earlier.

To the far right of the two c.1865 hand-hammered gutty balls and the John Gourlay feather ball (all of which still retain their original white paint) is what appears to be a smooth gutty ball. This one features a raised ring, or molding fin, around its equator. As shown in this section, some original smooth gutty balls have this fin, while others do not. The presence or absence of the fin depends on how well the ball was trimmed after being removed from the mold. On its own, the fin doesn't provide definitive proof of age. Both smooth gutty golf balls and smooth play balls were made with and without this fin around the equator. When combined with other characteristics, however, the fin can help support a nineteenth century date for a ball.

Above are two red-painted smooth gutties and part of a hand-hammered Forgan pattern gutty. Smooth gutties were, in rare instances, painted red. While quite uncommon, red golf balls from the 19th century were used in snow, frost, and when daisies were out in force.

Above left is a line-cut gutty ball by Allan Robertson, the remains of the "Allan" stamp still visible. One can see the oxidation and deterioration of the gutta percha where the paint has chipped off the ball. The ball to the right is an unnamed line-cut gutty ball. The oxidation at the top of this ball is clear evidence of its great age. The lines are typical of what a vertical line-cut gutty from the 1850s looks like. Both balls bear their original paint, which helps us understand what the original paint can (but not must) look like on a ball of similar age.

Above are two views of this early hand-scored smooth gutty made by Tom Morris. This ball has important evidence of its age. The paint is chipped in places to reveal gutta percha underneath, some of which has started to oxidize. This is important because the “T Morris” stamp has been redone and you can find it marked on replica feather balls made today, etc. However, on a ball that has all the characteristics of a genuinely old gutta percha ball, the T. Morris stamp gives it an iron clad provenance. As condition goes for a gutty ball with 170-year-old paint, this ball is fabulous!

Above are two more balls that started life as smooth gutties before being scored and then painted. The Allan ball on the left has vertical lines cut/hammered into its surface. The Willie Dunn ball on the right has been hand-hammered, but with a more complex pattern. These are fabulous balls in supreme condition, all things considered. They, along with all the other genuine balls in this section, show what genuine gutty balls from the 1840s-50s look like, and they set a standard for authenticity that so many of the balls in the previous section do not achieve.

Above, the Kempshall Click to the left and the Climax in the middle are rubber core balls that have a gutta percha cover. The Harry B. Wood labeled FlyAnPutt ball on the right, with its unique pattern of dashes and dots, is a solid gutta percha ball.

From this picture we see that the gutta percha in the solid gutty balls of the 1890s and the gutta percha covers of the early rubber core balls were pretty much the same, especially if pure gutta percha was used. We also see that gutta percha in outstanding condition tends to remain in outstanding condition. Gutta percha balls that have been damaged, however, tend to deteriorate/oxidize where the damage is located.

Any examination of what appears to be a genuine smooth gutty ball from around 1850 requires the collector to weigh the odds. Authenticity is rarely confirmed with absolute certainty; instead, it rests on a balance of evidence. The more details that align on the "old" side of the ledger—material, weight, wear, provenance—the stronger the case for authenticity. But even if 80% of the signs point to it being the real thing, 80% is not 100%. Ultimately, the collector must decide how comfortable they are with the odds before making an acquisition.

Making a smooth gutta percha ball today isn’t especially difficult, and that’s worth understanding—it’s been done before, and it’ll likely be done again. The process itself is fairly straightforward. First, you’ll need a smooth gutty ball mold and ball press, both of which are still available at antique golf auctions on occasion. Some enthusiasts have even used 3D printing to create suitable molds. Next, you need to source gutta percha, either by finding an old ball or combining a few worn ones—these aren’t hard to come by. Strip off the paint, melt the material by placing it in hot (not boiling) water, and roll the softened mass into a ball slightly larger than needed. Press it firmly to eliminate air pockets and ensure there are no folds. While still warm and pliable, place the material into the mold, screw the press tight, and let it cool for a few minutes.

Once cooled and removed from the mold, the ball will look freshly made. To simulate age, it needs to be distressed: knocked around to pick up small dings, marked with tools to mimic wear, and dirtied with dust or rottenstone. Still, in my experience, the result doesn’t quite pass the sniff test. The untouched portions of the ball lack the tiny hairline cracks typical of age and have a shinier, more plasticky appearance. And the fake strike marks often betray themselves—the tooling tends to create symmetrical raised edges, unlike the curved, uneven gashes made by clubheads. (Think of those classic smile marks on balata balls, or just look at any hacked up old gutta percha ball—there are a couple in the Ball grouping with the green grass background towards the end of section 5.1a.) These subtle differences in how the material behaves and records wear patterns are difficult to fake—and so far, I haven’t seen one that truly fools a trained eye.

For more on genuine smooth gutta percha balls, see my article Smooth Gutty Ball c.1848 also posted on this site.

6.1 Corrugated Play Balls ↩

The front row above displays seven balls of various sizes that appear to be Cigol or Paramount corrugated play balls, with the possible exception of the second ball, which bears the outline of a star on its pole. The ball on the far right measures 1.87 inches in diameter and weighs 2.74 ounces. The ball on the far left measures 1.47 inches and weighs 1.44 ounces. All the balls are hard and solid, but none are as resilient as a solid gutta percha golf ball when lightly dropped from a height of ¼ inch onto a hard surface. Some land with a distinct click, while others land with more of a thud—evidence that age has significantly diminished their elasticity.

7.1 Bantam & Golf Design Play Balls ↩

In the front row, a Paramount Bantam Design ball appears on the far left. Four Cigol "Golf Ball" designs, discussed earlier, are positioned in the center of the row. On the far right is a ringed bramble design from an unknown play ball maker. This ball measures 1.81 inches in diameter and is quite hard, though the surface yields ever so slightly when compressed between the thumb and forefingers—a characteristic of India rubber that has hardened with age but retains a trace of its original pliability.

8.1 Bramble Style Play Balls ↩

The second ball from the left in the front row is a Paramount golf ball design play ball. The remaining balls in this row are various solid bramble-style hard rubber balls, most likely not made by Paramount. Their diameters range from 1.38 inches on the far left to 1.61 inches on the far right. The lightest ball in the front row, third from the left, weighs just 0.93 ounces, while the heaviest, third from the right, weighs 1.72 ounces. When lightly bounced, some produce the distinctive sound of solid gutta percha, while others do not—indicative of differences in composition.

9.1 Two Real Golf Balls & Two Wannabes ↩

On the far left is a 1933 U.S. Royal golf ball measuring 1.62 inches in diameter—typical of the British "small ball." On the far right is the 1913 Chemico Bob golf ball that measures 1.67 inches. These serve as reference points, representing the standard size range for golf balls of the era.

Between them are two balls that resemble golf balls but deviate notably. The dimpled ball is significantly smaller and made of hollow metal, clearly not intended for regulation play. The mesh-patterned ball, featuring a hand-crafted design, is hard and produces a sound and bounce similar to gutta percha. However, at just 0.83 ounces and slightly compressible between the thumb and fingers, it appears to be made from para rubber that has hardened over time. Its purpose is unclear—it may have been a child's toy, a handmade undersized practice ball, or simply a play ball hand-crafted to resemble a golf ball.

Only three of the balls above are actual golf balls: the Silvertown mesh pattern in the top row and the US Royal and Chemico Bob on the respective ends of the bottom row. All of the balls are solid except for the Gutta Percha Company play ball second from the right in the back row and the metal dimple ball second from the left in the front row. The mesh ball in the front row also appears to be solid, but it is very lightweight for its size. The weight of all the non-golf balls, even those that are the same approximate size, can have major variances.

10.1 Baseball Cores ↩

This baseball core was produced under U.S. Patent No. 917,818 issued to John V. Riley on April 6, 1909. It measures approximately 1⅜ inches in diameter and weighs 1 ounce. According to Riley's patent, the core could be constructed solid or hollow. If hollow, it could be filled with fluid to adjust resilience and weight.

Given this information, the small black bramble ball located at the front left of the second row (from the bottom) in the image referenced earlier might also be a baseball core. It measures 1.345 inches in diameter and weighs 1.04 ounces. Though it appears to be made of gutta percha—based on its look and the sound it makes when bounced—aged solid India rubber can also be hard and appear black.

A related patent by Benjamin Shibe (U.S. Patent No. 924,696, issued June 15, 1909) also concerned "playing balls, and . . .more particularly to baseballs." Shibe noted that prior to his invention, the core of a baseball typically consisted of solid India rubber [italics mine] wound with layers of yarn. This is a very telling statement that speaks to a large production of solid rubber balls just in the world of baseballs. Shibe's patent describes a cork center encased tightly in a rubber layer, allowing for the yarn to be firmly wound around the core.

11.1 Conclusion ↩

This report provides but a cursory glance at the many reasons small balls were manufactured a century or more ago. Game balls specifically, for example, received only brief mention, yet they represent a broad genre of their own. Still, the evidence presented here makes it clear that many solid rubber and gutta-percha balls produced after 1850—despite closely resembling golf balls—were never intended for the game. Rather, they represent a wide range of children's toys, game balls, baseball cores, novelty items, and who-knows-what that were manufactured during a period of rapid industrial innovation and growing consumer demand.

With their varied compositions, irregular weights, and often whimsical surface patterns, these many and varied balls served diverse roles far removed from the thoughtfully designed and purposely constructed golf balls of their era. Yet, because so many mimic the size and appearance of true golf balls, collectors and historians today often find them perplexing. Distinguishing genuine antique golf balls from lookalikes is essential—not only for correctly identifying the artifacts of the game but also for appreciating the broader culture of recreation, play, and manufacturing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

My intention in writing this article is to simply share what experience and research has taught me on this topic. My hope is that it proves beneficial to the golf collecting community.

THANK YOU to Dr. Elmer Nahum, Dr. George Petro, Dr. Mark Hambly, and Jim Leaptrott for reviewing this article and staying awake long enough to respond. Brave souls, indeed. Also, an oversize Thank You to my wife, Cecelia, for proofreading this many times through all its iterations. Her tolerance for the arcane is exceeded only by her bravery to smile through it—and my wisdom to stop giving her more to read.

Special Thank You to Blake Giunta for designing, prepping, and posting this article on the web.

FOOTNOTES

- In fact, it seems unlikely, as no references to such a ball have been found. If one were to be discovered, it would not have a smooth surface, since by 1860, gutta-percha golf balls were already being sold with cut and patterned surfaces. Return ↩

- By the mid to late 1850s, other gutta percha manufacturers had been formed. The Gutta Percha Company was still the dominant maker in the industry, but the monopoly feeling had faded. Return ↩

- The gutta percha golf ball was invented by Robert A Patterson of St. Andrews in 1845. John Patterson, Robert's brother living in Edinburgh, improved the ball—made it more durable and less susceptible to cracking—and produced the first ones ever sold. This occurred before the Gutta Percha Company began selling gutta percha golf balls in early 1848. Section 5b of this article covers this in greater detail. Return ↩

- This ball is neither a golf ball nor a croquet ball, nor is there any other apparent use of this ball other than as a play ball which is the only other type of ball advertised, at least early on. If this ball is not a play ball, then that simply shows that more balls were made that approached the size of a golf ball and had a smooth gutta percha exterior. Return ↩

- The weight of solid gutty balls can vary as pockets of air would sometimes form when the ball was molded. Furthermore, the density of gutta percha golf balls could vary due to different source trees, processing differences, added materials such as were used in the Eclipse ball, molding conditions, etc. Two early square mesh molded balls circa 1880 I recently measured were 48.08 grams (1.69" diameter) and 49.32 grams (1.63" diameter), respectively. These are abnormally heavy by 1890s standards, but in keeping with an "Allan 30" feather ball I recently measured that came in at 48.24 grams (1.76/1.82 diameter). Return ↩

-

The list of twelve balls was made to show some of the balls that might relate to the Haskell Golf Ball Patent case then underway in the UK. The list is as follows:

- In 1844 T. Forster used rubber in admixture with other substances as a composition for making moulded balls.

- In 1858 G. Cuppers described of hardening (vulcanising) rubber and moulding it into balls.

- In 1860 R. Vivian coated central cores with rubber or vulcanised rubber.

- In 1860, also, H. Nicholson also made balls with or without a central core, bound with cotton or other threads or twine, and encased in gutta-percha, the whole being compressed. [This ball was patented in the UK and mentioned earlier in this article.]

- In 1866 C. Huntley made balls of a certain foundation compressed into a state of density by windings of worsted and covered with rubber. In 1867 Clark made use of rubber thread in a state of tension or stretch, for giving motion to mechanical toys.

- In 1868 H. A. Alden described balls comprising rubber as a constituent, the core being encased in windings of wire, twine, or cord.

- In 1869 Wolfgang surrounded certain cores of cricket balls with wound canvas or other material and then covered them with India rubber.

- In 1875 MacLellan made a compound containing India rubber, which he then vulcanised and turned into balls.

- In 1876 Woodward built up solid balls in sections by starting with a small round ball of rubber which he surrounded in successive stages with further rubber, vulcanising at each and, by heating, rendered homogeneous.

- In 1877 W. Currie patented golf balls having India rubber cores and centred in india rubber, and also the means of vulcanising them.

- In 1878 N. P. Fouquerolle described solid balls made out of strips of rubber by a rolling or winding process, and subjected to heat and pressure.

- In 1883 T. Burbridge made hollow balls of unvulcanised rubber covered or bound with "elastic" twill (prepared with rubber).

- The June 15, 1912 issue of "The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer" confirms that Cigol's Golf Ball was made of a hard and durable gutta percha compound and "retails for 10 cents." Return ↩

- Of course, there are outliers—smaller golf balls made for kids and parlor golf games, and larger balls made to test the market. Return ↩

- At 5.862 oz the weight of this ball matches the center of the range of what a solid 2 ½" ball made from gutta percha should weigh. Return ↩

- Composite golf balls were described in D. Stewart's August 31, 1876 UK patent application that called for mixing additives such as "cork, metal fillings, etc" into the gutta percha. William Currie's Dec. 20, 1877 patent application for his Eclipse ball called for using ground cork, ground leather, vegetable fibers, etc. as additives mixed into the gutta percha. I have not seen or heard of a ball produced by Stewart. Currie's ball was produced for approximately 20 years. Return ↩

- William Currie's Dec. 20, 1877 patent application for his Eclipse ball called for using "ground cork, ground leather, vegetable fibers, etc." as additives mixed into the gutta percha. The use of filler material primarily saved the ball maker money as gutta percha was expensive, but the maker wanted the ball to appear like it was still of the same high quality as any pure gutta percha golf ball. Return ↩

- The gutta percha balls produced between the early 1850s and late 1870s were originally molded with a smooth outer surface that was then either scored by hand or with a cutting lathe. Most likely a few balls produced during this period were never completed, left behind with an unscored, smooth surface. But this would be a small number if and when that happened. By 1880, molds were being used to mold lines into the ball's surface. Return ↩

- I have personally examined both the Bakelite bagatelle balls and the wooden ball which I believe is an old bagatelle ball. The Bakelite balls are much too heavy and hard to be golf balls. Return ↩

- Any claims of someone finding a 15th century wooden golf ball, or something to that effect, would be right up there with locating the Loch Ness monster. Such a claim would require an ironclad provenance (proof) to be legitimate. Return ↩

- One website I located offered sets of "Old English Bagatelle" balls, each set consisting of 4 red, 8 white, and 1 black ball. Sizes included 1 5/8" (1.625") which falls within the size range of a golf ball. Return ↩

- During the 19th century, most homes in the UK were heated by burning coal in fireplaces. This produced sulfur compounds in the air, which could react with lead-based paint over time—especially under certain environmental conditions. Shown below at the end of the footnotes, left to right, are a solid gutty, a hand-hammered gutty, and a feather ball with varying degrees of discoloration to their original paint, no part of which has been altered or disturbed beyond normal wear since it was applied. These balls remain highly collectible as their names and patterns are strong and clear, and nobody has altered their original condition. Return ↩

-

It has a small production hole on the side of the equator, where a straight pin can be inserted into the ball without any resistance, confirming that it is hollow.

Return ↩

Return ↩